Evidence Dialogues: Improving programming to address gender inequality in fragile contexts

By now, virtually everyone in the development community recognizes the centrality of gender equality in improving lives. Now the question is: how can interventions be designed to effectively move the needle on entrenched gender prejudice?

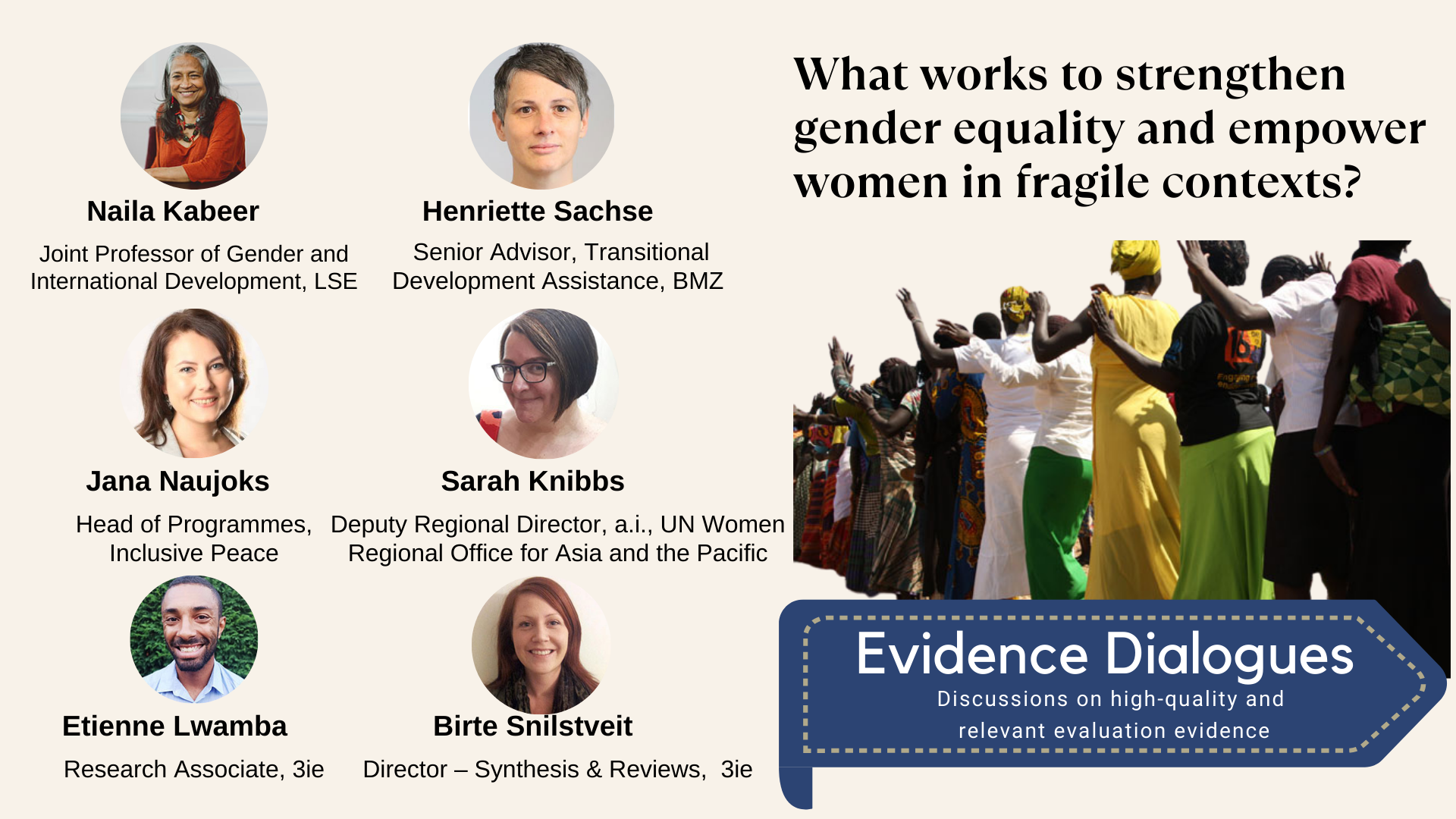

Gender and development programming experts gathered on 28 October 2021 for our Evidence Dialogues webinar to discuss how to use the findings from 3ie’s recently-published systematic review (discussed in this blog post) to improve gender-focused programming in fragile contexts. The review synthesized findings from 104 studies on 14 different types of gender-sensitive and gender-transformative interventions in 29 countries.

In general, the review found that several common types of programming, such as cash transfers, had positive effects. These findings can help put debates about those types of interventions to rest, said Henriette Sachse, Senior Advisor, Transitional Development Assistance, BMZ.

“When it comes to cash transfers, there were a lot of discussions going on,” Sachse said. “I’m especially happy that the findings are so strong that cash is a very good way [to intervene], especially to also strengthen gender equality and women’s empowerment.”

Interventions often succeeded in achieving their most immediate aims, but many times they were not able to produce the downstream effects they were looking for, said 3ie Research Associate Etienne Lwamba, the review’s lead author.

As one example, technical and vocational education and training (TVET) programs showed evidence of increasing skills and knowledge among participants – but those skills were not always translating into employment, Lwamba said. The blockage often seemed to be cultural.

“Norms in restrictive social contexts can act as a barrier to empowerment,” Lwamba said.

Of course they are, said Naila Kabeer, joint professor of gender and international development at the London School of Economics.

“The barriers to realizing the kinds of impacts you’re looking for are very often these social constraints,” Kabeer said. “In a sense, that is the nature of the problem.”

These findings highlight the importance of including men – husbands, fathers-in-law, religious leaders – in order to avoid backlash from programming focused on women, said Jana Naujoks, Head of Programmes for Inclusive Peace.

On this point, Kabeer said she was a bit conflicted.

“I understand the problem on the ground, [but] it always troubles me that we’re trying to ask the gatekeepers of patriarchal power to open up the gates,” Kabeer said.

Another problem with addressing deep issues of gender inequality is the short timelines that projects are required to follow, panelists agreed.

“The principal frustration for people doing the work is ‘We don’t have enough time!'” said Sarah Knibbs, Deputy Regional Director a.i., UN Women Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific. “Sometimes we give people money for a year, and then we ask them to show they’ve changed a community.”

The short timelines may be why the review’s findings show many more effects on immediate outcomes rather than downstream effects.

“It’s not a quick fix,” Naujoks said. “We can do quick things in 18 months or two years, but we can’t get to root causes.”

To hear more details, watch the full discussion here.