Peacebuilding programs are stronger when informed by evidence, despite the constraints of their environments

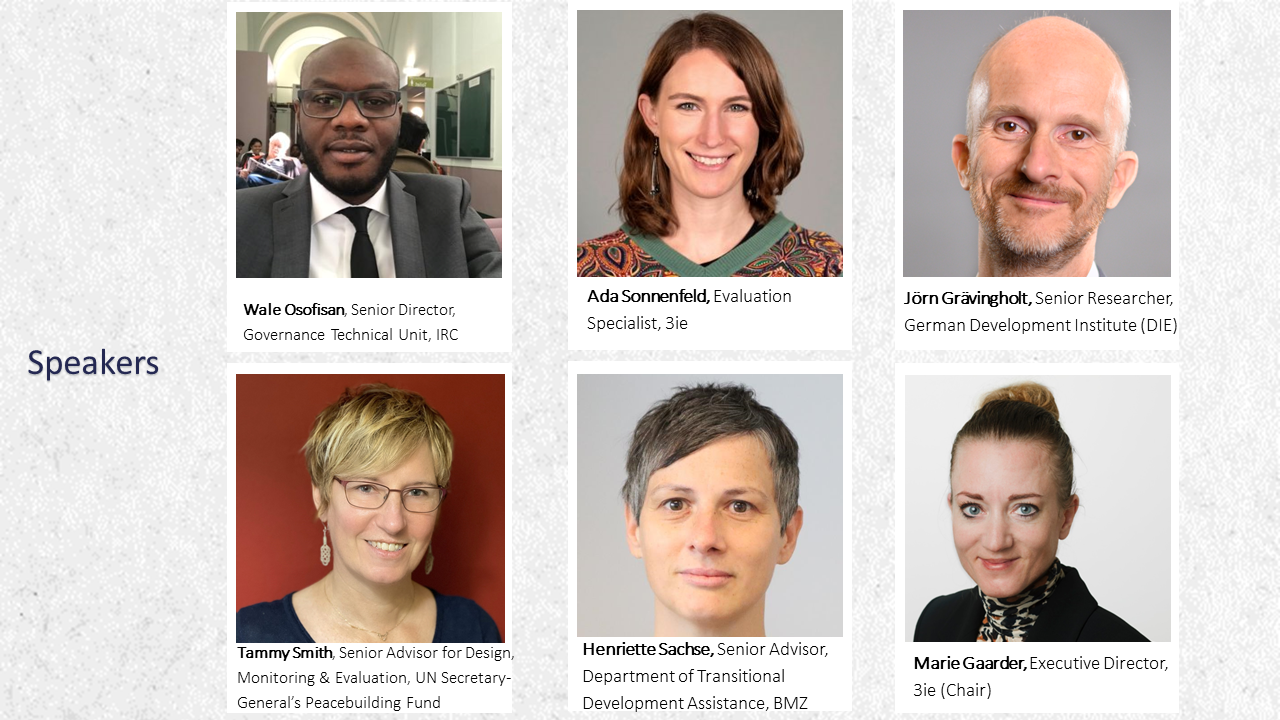

In response to new and ongoing violent conflicts, the international community increasingly reacts not just with humanitarian aid, but also with innovative transitional assistance and peacebuilding programs. In 3ie’s inaugural Evidence Dialogue webinar, our panel of experts discussed some new evidence about effective peacebuilding approaches, the role of evidence in designing peacebuilding programming, and the constraints which make both implementation and evaluation difficult.

“We cannot afford to assume that [peacebuilding] programs work,” said Marie Gaarder, 3ie’s Executive Director. “The cost of ineffective and failing programs is simply too high.”

Some new evidence comes from a forthcoming 3ie systematic review which draws together 24 separate studies investigating interventions to improve social cohesion in conflict-affected settings.

The review shows that several types of social cohesion interventions yielded positive results. Programs encouraging collaborative contact between opposing sides of a conflict increased people’s willingness to participate in social or political processes. Other interventions which combined workshops, inter-group contact and economic support resulted in increased trust, as did media-for-peace interventions such as specially-produced radio dramas. Also, some school-based peace education programs yielded positive effects on participants’ reported trust and willingness to help others, said Ada Sonnenfeld, a 3ie evaluation specialist and lead author of the review.

Where programs were not successful, sometimes it was because of a failure to adapt to local conditions, Sonnenfeld said.

“Very few of the studies undertook conflict assessments,” Sonnenfeld said. “There were many situations in which there were issues in identifying the appropriate bottleneck to intergroup social cohesion at a local level.”

That variation in local conditions can make the difference between success and failure, said Wale Osofisan, senior director of the International Rescue Committee’s Governance Technical Unit.

“What we also try to do is not just try to learn what works, but under what conditions, by what mechanisms do [programs] work,” Osofisan said. “An intervention might work in Northeast Uganda and it might fail in Northwest Uganda.”

It is important to remember that the very circumstances necessitating peacebuilding interventions also affect the interventions themselves and any research about them, said Jörn Grävingholt, a senior researcher for the German Development Institute (DIE).

“Difficult environments are not only difficult to act in, but also difficult environments [in which to] create evidence,” Grävingholt said. “High physical insecurity is obviously a challenge.”

Political realities also affect which peacebuilding programs can be implemented, said Tammy Smith, senior advisor for design, monitoring, and evaluation of the United Nations Secretary General’s Peacebuilding Fund.

“As much as we would love to say all of our decisions are firmly rooted in evidence, part of our decisions are also balanced by political considerations,” Smith said.

Panelists also agreed on the need to aim for a holistic, integrated approach to peacebuilding. But while solving conflicts completely would be the best option, sometimes building individual and community resilience in the interim is also necessary, said Henriette Sachse, a senior advisor at the Department of Transitional Development Assistance under the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ).

“At the moment, we look at a lot of conflicts we call protracted crises,” Sachse said. “It’s really helpful to see what people need, how we can strengthen their resilience.”

And the international community can only do so much, all panelists agreed.

“We have to accept the fact that whenever we talk about peacebuilding and everything related to issues of war and peace, external support can only be a tiny part of the puzzle,” Grävingholt said. “Most of the heavy lifting always has to be done by the societies themselves.”