Women’s empowerment requires more than just economic resources

Although women’s economic empowerment has received increased attention from policymakers in the last decade, progress remains frustratingly slow. Gaps in wages, education, autonomy, and social status remain.

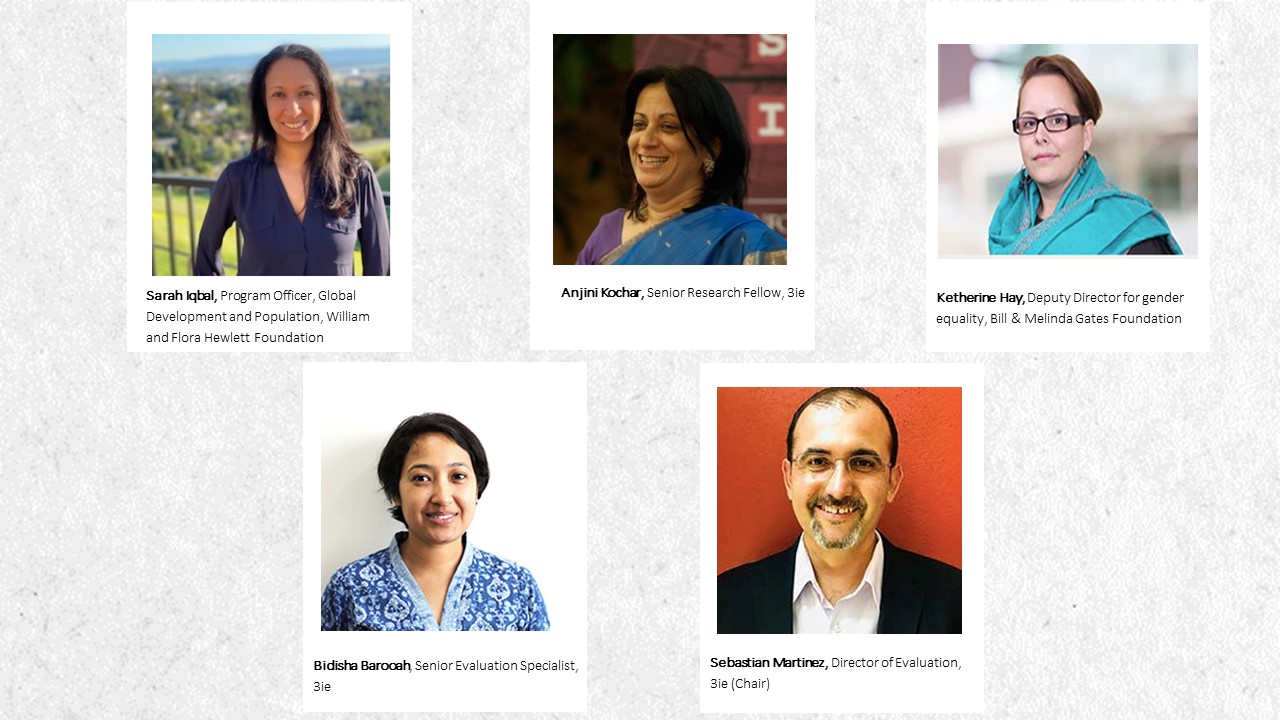

More than 250 people joined Thursday’s 3ie Evidence Dialogue webinar to discuss the barriers blocking women’s economic, social, and personal empowerment, as well as promising approaches to overcoming them.

“It’s going to take us hundreds of years to close those gaps at the current pace of change, so it’s really important for us to try to understand what those barriers are,” said Katherine Hay, deputy director for Gender Equality at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. “We don’t really understand as deeply as we need to how they’re perpetuated over time.”

Evaluation research conducted by 3ie about India’s National Rural Livelihoods Mission shows how some progress can be made, as well as illustrating the difficulty in holistically improving women’s lives, said 3ie Senior Evaluation Specialist Bidisha Barooah.

“The overall results are very encouraging” she said. “The program led to large increases in household income.”

In particular, loans and access to government services were effective at improving women’s income. However, there was no improvement in women’s bargaining position within the household, where men continued to hold disproportionate decision-making power.

“What was really surprising for us [was the absence of] impact on women’s decision making in the household,” Barooah said. “We have to examine why we did not see this.”

New research from 3ie Senior Research Fellow Anjini Kochar proposes an answer: incremental changes in women’s economic opportunities do not change the household balance of power until a key threshold is crossed.

“Small changes that still leave women more dependent on the marriage than a man will still not change their bargaining power,” Kochar said. “Small incremental changes will have no impact [on household bargaining] unless they accumulate over time.”

Programs may also need to incorporate men in order to have benefits for women, because men are often important in enforcing gender norms that restrict women’s opportunities, Barooah said.

“Where men can be brought in is actually at the mobilization and the training phase so they can understand what is in it for them and why women’s empowerment in itself is good for their families and their societies,” Barooah said.

The different lived realities of women need to be considered in policymaking, said Sarah Iqbal, program officer for global development and population at the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation.

“Women are different from men,” Iqbal said. “If that doesn’t get considered at the outset, then women get left out.”

For those interested in the National Rural Livelihoods Mission, previous posts on this blog have discussed its effectiveness, approach, and potential to do more.